As software engineers, we often rely on libraries to streamline our development process and enhance our applications. However, creating and maintaining a library comes with great responsibility. In this post, we’ll explore five essential practices that every library developer should follow to ensure their code remains stable, reliable, and user-friendly.

Before we dive in, let’s consider this famous quote from Linus Torvalds, the creator of Linux:

“WE DO NOT BREAK USERSPACE!”

This statement encapsulates a core principle of software development, especially relevant to library creators. It underscores the importance of maintaining compatibility and stability for the end-users of our code.

1. Preserve Contract Integrity: No Breaking Changes

The cardinal rule of library development is to never introduce breaking changes to your public contracts. This means:

- Use method overloads instead of modifying existing signatures

- Add new properties rather than altering existing ones

- Think critically about your public interfaces before implementation

Remember, the urge to “make the code cleaner” is rarely a sufficient reason to break existing contracts. Put more effort into designing robust public interfaces from the start.

Code Examples

Let’s look at some examples in Kotlin to illustrate how to preserve contract integrity:

C# Examples

using System;

// Original version

public class UserService

{

public void CreateUser(string name, string email)

{

// Implementation

}

}

// Good: Adding an overload instead of modifying the existing method

public class UserService

{

public void CreateUser(string name, string email)

{

// Original implementation

}

public void CreateUser(string name, string email, int age)

{

// New implementation that includes age

}

}

// Bad: Changing the signature of an existing method

public class UserService

{

// This would break existing code

public void CreateUser(string name, string email, int age)

{

// Modified implementation

}

}

// Good: Adding a new property instead of modifying an existing one

public class User

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public string Email { get; set; }

public DateTime CreatedAt { get; set; } = DateTime.UtcNow; // New property with a default value

}

// Better: Avoid using primitives in parameters

public class UserService

{

public void CreateUser(User user)

{

// Modified implementation

}

}

2. Maintain Functional Consistency

Contract changes are the basic one that people are usually aware of, functional changes are changes that change what you expect from a library under a given condition, this is a little harder, but again its a simple practice to follow to achieve it.

Functional consistency is crucial for maintaining trust with your users. To achieve this:

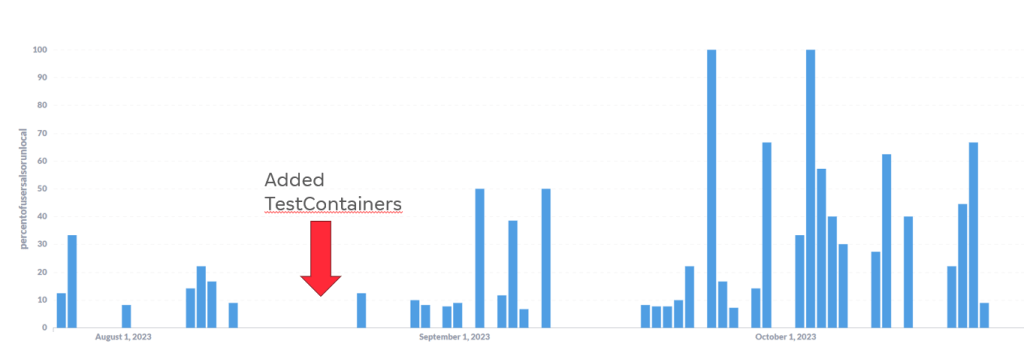

- Have good test coverage

- Only add new tests; never modify existing tests

This approach ensures that you don’t inadvertently introduce functional changes that could disrupt your users’ applications.

3. Embrace the “Bug” as a Feature

Counter-intuitive as it may seem, fixing certain bugs can sometimes do more harm than good. Here’s why:

- Users often build their code around existing behavior, including bugs

- Changing this behavior, even if it’s “incorrect,” can break dependent systems, and cause more problems than you fix

Unless you can fix a bug without modifying existing tests, it’s often safer to leave it be and document the behavior thoroughly.

4. Default to Non-Public Access: Minimize Your Public API Surface

When developing libraries, it’s crucial to be intentional about what you expose to users. A good rule of thumb is to default to non-public access for all elements of your library. This approach offers several significant benefits for both library maintainers and users.

Firstly, minimizing your public API surface provides you with greater flexibility for future changes. The less you expose publicly, the more room you have to make internal modifications without breaking compatibility for your users. This flexibility is invaluable as your library evolves over time.

Secondly, a smaller public API reduces your long-term maintenance burden. Every public API element represents a commitment to long-term support. By keeping this surface area minimal, you effectively decrease your future workload and the potential for introducing breaking changes.

Lastly, a more focused public API often results in a clearer, more understandable interface for your users. When users aren’t overwhelmed with unnecessary public methods or properties, they can more easily grasp the core functionality of your library and use it effectively.

To implement this principle effectively, consider separating your public interfaces and contracts into a distinct area of your codebase, or even into a separate project or library. This separation makes it easier to manage and maintain your public API over time.

Once an element becomes part of your public API, treat it as a long-term commitment. Any changes to public elements should be thoroughly considered and, ideally, avoided if they would break existing user code. This careful approach helps maintain trust with your users and ensures the stability of projects that depend on your library.

In languages that support various access modifiers, use them judiciously. Employ ‘internal’, ‘protected’, or ‘private’ modifiers liberally, reserving ‘public’ only for those elements that are explicitly part of your library’s interface. This practice helps enforce the principle of information hiding and gives you more control over your library’s evolution.

For the elements you do make public, provide comprehensive documentation. Thorough documentation helps users understand the intended use of your API and can prevent misuse that might lead to dependency on unintended behavior.

Consider the following C# example:

// Public API - in a separate file or project

public interface IUserService

{

User CreateUser(string name, string email);

User GetUser(int id);

}

// Implementation - in the main library project

internal class UserService : IUserService

{

public User CreateUser(string name, string email)

{

// Implementation

}

public User GetUser(int id)

{

// Implementation

}

// Internal helper method - can be changed without affecting public API

internal void ValidateUserData(string name, string email)

{

// Implementation

}

}

In this example, only the IUserService interface is public. The actual implementation (UserService) and its helper methods are internal, providing you with the freedom to modify them as needed without breaking user code.

Remember, anything you make public becomes part of your contract with users. By keeping your public API surface as small as possible, you maintain the maximum flexibility to evolve your library over time while ensuring stability for your users. This approach embodies the spirit of Linus Torvalds’ mandate: “WE DO NOT BREAK USERSPACE!” It allows you to respect your users’ time and effort by providing a stable, reliable foundation for their projects.

6. Avoid Transient Dependencies: Empower Users with Flexibility

An often overlooked aspect of library design is the management of dependencies. While it’s tempting to include powerful third-party libraries to enhance your functionality, doing so can lead to unforeseen complications for your users. Instead, strive to minimize transient dependencies and provide mechanisms for users to wire in their own implementations. This approach not only reduces potential conflicts but also increases the flexibility and longevity of your library.

Consider a scenario where your library includes functions for pretty-printing output. Rather than hardcoding a dependency on a specific logging or formatting library, design your interface to accept generic logging or formatting functions. This allows users to integrate your library seamlessly with their existing tools and preferences.

Here’s an example of how you might implement this in C#:

// Instead of this:

public class PrettyPrinter

{

private readonly ILogger _logger;

public PrettyPrinter()

{

_logger = new SpecificLogger(); // Forcing a specific implementation

}

public void Print(string message)

{

var formattedMessage = FormatMessage(message);

_logger.Log(formattedMessage);

}

}

// Do this:

public class PrettyPrinter

{

private readonly Action<string> _logAction;

public PrettyPrinter(Action<string> logAction)

{

_logAction = logAction ?? throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(logAction));

}

public void Print(string message)

{

var formattedMessage = FormatMessage(message);

_logAction(formattedMessage);

}

}

// Or this: (When the framework has support for generic implementations like logging and DI)

public class PrettyPrinter

{

private readonly ILogger _logger;

public PrettyPrinter(ILogger<PrettyPrinter> logger)

{

_logger = logger ?? throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(logger));

}

public void Print(string message)

{

var formattedMessage = FormatMessage(message);

_logger.LogInformation(formattedMessage);

}

}

In the improved version, users can provide their own logging function, which could be from any logging framework they prefer or even a custom implementation. This approach offers several benefits:

- Flexibility: Users aren’t forced to adopt a logging framework they may not want or need.

- Reduced Conflicts: By not including a specific logging library, you avoid potential version conflicts with other libraries or the user’s own code.

- Testability: It becomes easier to unit test your library without needing to mock specific third-party dependencies.

- Future-proofing: Your library remains compatible even if the user decides to change their logging implementation in the future.

This principle extends beyond just logging. Apply it to any functionality where users might reasonably want to use their own implementations. Database access, HTTP clients, serialization libraries – all of these are candidates for this pattern.

By allowing users to wire in their own dependencies, you’re not just creating a library; you’re providing a flexible tool that can adapt to a wide variety of use cases and environments. This approach aligns perfectly with our overall goal of creating stable, user-friendly libraries that stand the test of time.

You can also consider writing extension libraries that add default implementations.

For example, your base Library MyLibrary doesn’t include a serializer, just the interface, and you create MyLibrary.Newtonsoft that contains the Newtonsoft Json serializer implementation for the interface in your library and wires it up for the user. This gives teh consumer the convenance of an optional default, but flexibility the change.

7. Target Minimal Required Versions: Maximize Compatibility

When developing a library, it’s tempting to use the latest features of a programming language or framework. However, this approach can significantly limit your library’s usability. A crucial principle in library development is to target the minimal required version of your language or framework that supports the features you need.

By targeting older, stable versions, you ensure that your library can be used by a wider range of projects. Many development teams, especially in enterprise environments, cannot always upgrade to the latest versions due to various constraints. By supporting older versions, you make your library accessible to these teams as well.

Here are some key considerations:

- Assess Your Requirements: Carefully evaluate which language or framework features are truly necessary for your library. Often, you can achieve your goals without the newest features.

- Research Adoption Rates: Look into the adoption rates of different versions of your target language or framework. This can help you make an informed decision about which version to target.

- Use Conditional Compilation: If you do need to use newer features, consider using conditional compilation to provide alternative implementations for older versions.

- Document Minimum Requirements: Clearly state the minimum required versions in your documentation. This helps users quickly determine if your library is compatible with their project.

- Consider Long-Term Support (LTS) Versions: If applicable, consider targeting LTS versions of frameworks, as these are often used in enterprise environments for extended periods.

Here’s an example in C# demonstrating how you might use conditional compilation to support multiple framework versions:

public class MyLibraryClass

{

public string ProcessData(string input)

{

#if NETSTANDARD2_0

// Implementation for .NET Standard 2.0

return input.Trim().ToUpper();

#elif NETSTANDARD2_1

// Implementation using a feature available in .NET Standard 2.1

return input.Trim().ToUpperInvariant();

#else

// Implementation for newer versions

return input.Trim().ToUpperInvariant();

#endif

}

}

In this example, we provide different implementations based on the target framework version. This allows the library to work with older versions while still taking advantage of newer features when available.

Remember, the goal is to make your library as widely usable as possible. By targeting minimal required versions, you’re ensuring that your library can be integrated into a diverse range of projects, increasing its potential user base and overall value to the developer community.

8. Internal Libraries: Freedom with Responsibility

Yes there’s a 8th, but it only applies to internal.

While internal libraries offer more flexibility, it’s crucial not to abuse this freedom:

- Use tools like SourceGraph to track usage of internal methods

- Don’t let this capability become an excuse to ignore best practices

- Strive to maintain the same level of stability as you would for public libraries

Remember, avoiding breaking changes altogether eliminates the need for extensive usage tracking, saving you time and effort in the long run.

Tips

- Set GenerateDocumentationFile to true in your csproj files, it will enable a static code analysis rule that errors if you don’t have xml comments for documentation of public methods. It will make you write documentation for all public methods that will help you think about “should this be public” and if the answer is yes think about the contract.

- Use Analyzers: Implement custom Roslyn analyzers, eslint, etc. to enforce your library’s usage patterns and catch potential misuse at compile-time. (Example)

- Performance Matters: Include benchmarks in your test suite to catch performance regressions early. Document performance characteristics of key operations.

- Version Thoughtfully: Use semantic versioning (SemVer) to communicate the nature of changes in your library. Major version changes should be avoided and reserved for breaking changes, minor versions for new features, and patches for bug fixes.

Conclusion

Developing a library is more than just writing code; it’s about creating a tool that empowers other developers and stands the test of time. By adhering to the golden rules we’ve discussed – from preserving contract integrity to targeting minimal required versions – you’re not just building a library, you’re crafting a reliable foundation for countless projects.

Remember, every public API you expose is a promise to your users. By defaulting to non-public access, avoiding transient dependencies, and embracing stability even in the face of “bugs,” you’re honoring that promise. You’re telling your users, “You can build on this with confidence.”

The words of Linus Torvalds, “WE DO NOT BREAK USERSPACE!”, serve as a powerful reminder of our responsibility as library developers. We’re not just writing code for ourselves; we’re creating ecosystems that others will inhabit and build upon.

As you develop your libraries, keep these principles in mind. Strive for clarity in your public interfaces, be thoughtful about dependencies, and always consider the long-term implications of your design decisions. By doing so, you’ll create libraries that are not just useful, but respected and relied upon.

In the end, the mark of a truly great library isn’t just in its functionality, but in its reliability, its adaptability, and the trust it builds with its users. By following these best practices, you’re well on your way to creating such a library. Happy coding, and may your libraries stand the test of time!