In our previous post, we explored the first set of essential skills for product engineers, focusing on non-technical abilities that bridge the gap between engineering and business. Today, we’ll dive into the second part of our essential skills series, covering more technically-oriented skills that are crucial for success in product engineering.

Data Analysis and Metrics

In the world of product engineering, data reigns supreme. This skill empowers engineers to make informed decisions, measure the impact of their work, and continuously improve product performance.

Metrics Definition is the foundation of effective data analysis. It’s not enough to simply collect data; you need to know which metrics are most relevant to your product and how they align with broader business goals. This requires a deep understanding of both the product and the business model. For instance, a social media application might focus on Daily Active Users (DAU) as a key engagement metric, along with other user interaction metrics like posts per user or time spent in the app. On the other hand, an e-commerce platform might prioritize conversion rates, average order value, and customer lifetime value. By defining the right metrics, engineers ensure that they’re measuring what truly matters for their product’s success.

The next step is Data Collection. This involves implementing systems to gather data accurately and consistently. It’s not just about collecting data, but ensuring its accuracy and integrity. Many engineers work with established analytics tools like Google or Adobe Analytics, which provide a wealth of user behavior data out of the box. However, for more specific or granular data needs, custom tracking solutions are necessary. This could involve instrumenting your code to log specific events or user actions. The key is to create a comprehensive data collection system that captures all the information needed to calculate your defined metrics.

With data in hand, the next skill is Statistical Analysis. While engineers don’t need to be statisticians, a basic understanding of statistical concepts is needed for interpreting data correctly. This includes grasping concepts like statistical significance, which helps determine whether observed differences in metrics are meaningful or just random noise. Understanding the difference between correlation and causation is also vital – just because two metrics move together doesn’t necessarily mean one causes the other. Handling outliers is another important skill, as extreme data points can significantly skew results if not treated properly. These statistical skills allow engineers to draw accurate conclusions from their data and avoid common pitfalls in data interpretation.

Data Visualization is where numbers transform into narratives. The ability to present data in clear, compelling ways is crucial for communicating insights to stakeholders who may not have a deep technical background. Tools like metabase, superset, grafana, etc offer powerful capabilities for creating interactive visualizations, while even simple Excel charts can be effective too. The goal is to make the data tell a story – to highlight trends, comparisons, or anomalies in a way that’s immediately understandable. Good data visualization can turn complex datasets into actionable insights, influencing product decisions and strategy.

A/B Testing is a technique in the engineer’s toolkit. It involves designing and implementing experiments to test hypotheses and measure the impact of changes. This could be as simple as testing two different button colors (one the A variant, the other the B) to see which drives more clicks, or as complex as rolling out a major feature to a subset of users to evaluate its impact on key metrics. Effective A/B testing requires understanding concepts like control groups (users who don’t receive the change), variable isolation (ensuring you’re testing only one thing at a time), and statistical power (having a large enough sample size to draw meaningful conclusions). Mastering A/B testing allows engineering teams to make data-driven decisions about feature development and optimization.

Performance Optimization

In today’s fast-paced digital world, user expectations for application performance have never been higher. Users demand fast, responsive applications that work seamlessly across devices and network conditions. As a result, performance optimization has become a critical skill for engineers. It’s not just about making things fast; it’s about creating a smooth, responsive user experience that keeps users engaged and satisfied, regardless of the complexity behind the scenes.

Profiling and Benchmarking form the foundation of effective performance optimization. Before you can improve performance, you need to understand where the bottlenecks are. This involves using a variety of tools to analyze your application’s performance characteristics. For front-end performance, browser developer tools provide powerful capabilities for analyzing load times, JavaScript execution, and rendering performance, chrome debugger and extensions allow testing stats like LCP, CLS, etc and debugging why they are bad locally, but don’t forget to measure RUM (Real User Metrics), getting data from your real user interactions. These tools can help identify slow-loading resources, long-running scripts, or inefficient DOM manipulations that might be causing performance issues.

On the backend, specialized profiling tools can help identify performance bottlenecks in server-side code or database queries. These tools like pyroscope, application insights and open telemetry tracing, might analyze CPU usage, memory allocation, or database query execution times to pinpoint areas for improvement. The key is to establish baseline performance metrics and then systematically identify the areas that have the biggest impact on overall application performance.

Once you’ve identified performance bottlenecks, the next step is applying Optimization Techniques. This is a topic for another post for sure, based on your environment this can vary greatly so I wont go into too much details today.

Google’s Core Web Vitals initiative is a prime example of the industry’s focus on performance and its impact on user experience. These metrics – Largest Contentful Paint (LCP), First Input Delay (FID), and Cumulative Layout Shift (CLS) – provide a standardized way to measure key aspects of user-centric performance. LCP measures loading performance, FID measures interactivity, and CLS measures visual stability. By focusing on these metrics, engineers can ensure they’re optimizing for the aspects of performance that most directly impact user experience.

For example, optimizing for Largest Contentful Paint might involve prioritizing the loading of above-the-fold content, while improving First Input Delay could involve breaking up long tasks in JavaScript to improve responsiveness to user interactions. Minimizing Cumulative Layout Shift often involves careful management of how content loads and is displayed, ensuring that elements don’t unexpectedly move around as the page loads.

The importance of these metrics extends beyond just providing a better user experience. Search engines like Google now consider these performance metrics as ranking factors, directly tying performance optimization to an application’s visibility and success.

Security and Privacy

Cyber threats are ever-evolving and privacy regulations are becoming increasingly stringent, security and privacy considerations must be at the forefront of a engineer’s mind. These are not just technical challenges, but fundamental aspects of building user trust and ensuring the long-term success of a product.

Threat Modeling is a proactive approach to security that involves anticipating and modeling potential security threats to your application. This process requires engineers to think like attackers, identifying potential vulnerabilities and attack vectors in their systems. It’s not just about considering obvious threats like unauthorized access, but also more subtle risks like data leakage or denial of service attacks. Effective threat modeling involves mapping out the system architecture, identifying assets that need protection, and systematically analyzing how these assets could be compromised. This process should be an ongoing part of the development lifecycle, revisited as new features are added or the system architecture evolves.

Secure Coding Practices are the foundation of building secure applications. This involves understanding and implementing best practices for writing code that is resistant to common security vulnerabilities. Input validation is a crucial aspect of this, ensuring that all data entering the system is properly sanitized to prevent attacks like SQL injection or cross-site scripting. Proper authentication and authorization mechanisms are essential to ensure that users can only access the resources they’re entitled to. Secure data storage practices, including proper encryption of sensitive data both at rest and in transit, are also critical. Engineers should be familiar with common security vulnerabilities (like those listed in the OWASP Top 10) and know how to mitigate them in their code.

Compliance Understanding has become increasingly important as privacy regulations have proliferated around the world. Engineers need at least a basic understanding of relevant privacy regulations like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe or the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) in the United States. This doesn’t mean engineers need to become legal experts, but they should understand how these regulations impact product development. For example, GDPR’s “right to be forgotten” requirement has implications for how user data is stored and managed. Understanding these regulations helps engineers make informed decisions about data handling and storage, and ensures that privacy considerations are factored into product design from the outset.

Security Testing is a important skill for ensuring that the security measures implemented are effective. This involves familiarity with various security testing tools and practices. Penetration testing, or “pen testing,” involves simulating attacks on a system to identify vulnerabilities. This can be done manually by security experts or using automated tools. Code security scanners are another important tool, analyzing code for potential security issues. Static Application Security Testing (SAST) tools can identify vulnerabilities in source code, while Dynamic Application Security Testing (DAST) tools can find issues in running applications. Engineers should be familiar with these tools and be able to interpret and act on their results.

Security and privacy are no longer optional considerations in engineering – they are fundamental requirements. As cyber threats continue to evolve and users become increasingly aware of privacy issues, the ability to build secure, privacy-respecting products will be a key differentiator for engineers.

Scalability and Reliability

As products grow and user bases expand, the ability to scale systems to meet increased demand while maintaining reliability becomes an important skill for engineers. This is not just about handling more users or data; it’s about ensuring that the product continues to perform well and provide a consistent user experience even as it grows exponentially.

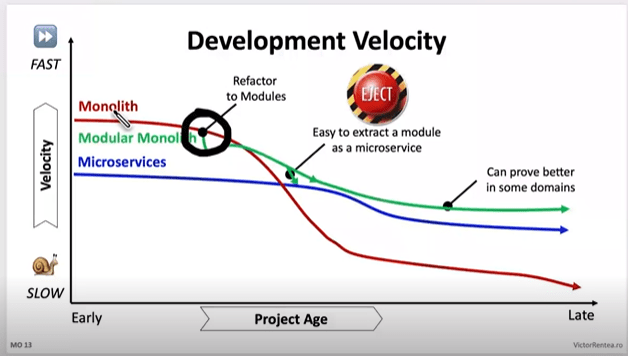

Distributed systems involve multiple components working together across different networks or geographic locations to appear as a single, cohesive system to end-users. This approach allows for greater scalability and fault tolerance, but it also introduces complexities in areas like data consistency, network partitions, and system coordination. Engineers need to understand concepts like CAP theorem, and it’s proponents. They should be familiar with patterns like microservices architecture, moduliths, event sourcing, etc. and how these apply with scale.

Load Balancing and Caching are critical strategies for managing increased demand on systems. Load balancing has changed greatly in recent years, gone are teh days of a large “in front everywhere” infrastructure, in favour of load balancing sidecars now with tech like envoy, and in-front load balancing banished to the edges. Engineers should be familiar with different load balancing algorithms (like round-robin, least connections, etc.) and understand when to use each as well as how health checks work in these scenarios.

Caching, on the other hand, could involve in-memory caches like Redis, content delivery networks (CDNs) for static assets, or application-level caching strategies. Effective caching requires careful consideration of cache invalidation strategies to ensure users always see up-to-date information. Engineers should understand not only pull through cache but other forms such as write-through, etc and also when to prewarm and expire based on the data and user needs.

Database Scaling is often one of the most challenging aspects of growing a system. As data volume and read/write operations increase, a single database instance may no longer be sufficient. Engineers need to be familiar with various database scaling techniques. Vertical scaling (adding more resources to a single machine) can work up to a point, but eventually, horizontal scaling becomes necessary and presents many challenges and options that engineers should be familiar with to be able to make the right choice.

Chaos Engineering is a proactive approach to ensuring system reliability that has gained prominence in recent years. The core idea is to intentionally introduce failures into your system in a controlled manner to test its resilience. This helps identify weaknesses in the system that might not be apparent under normal conditions.

Netflix’s Chaos Monkey is a prime example of this approach. This tool randomly terminates instances in their production environment, forcing engineers to build systems that can withstand these types of failures. By simulating failures in a controlled way, Netflix ensures that their systems can handle unexpected issues in real-world scenarios.

Other forms of chaos engineering might involve simulating network partitions, inducing latency, or exhausting system resources. The key is to start small, build confidence, and gradually increase the scope of these experiments. This approach not only improves system reliability but also builds a culture of resilience within engineering teams.

The importance of scalability and reliability in product engineering cannot be overstated. As users increasingly rely on digital products for critical aspects of their lives and work, the cost of downtime or poor performance can be enormous, both in terms of lost revenue and damaged user trust.

Moreover, the ability to scale efficiently can be a key competitive advantage. Products that can quickly adapt to growing demand can capture market share and outpace competitors. On the flip side, products that struggle with scalability often face user frustration, increased operational costs, and missed opportunities.

Continuous Integration and Deployment (CI/CD)

CI/CD practices enable teams to deliver code changes more frequently and reliably, accelerating the feedback loop and reducing the risk associated with deployments.

Engineers need to be proficient in writing effective, efficient tests and understanding concepts like test coverage and why the test pyramid is flawed, and new concepts like the testing honey combe. They should also be familiar with testing frameworks and tools specific to their technology stack. The goal is to catch bugs early in the development process, reducing the cost and risk of fixing issues in production.

Continuous Integration (CI) means continuously integrating code, its not about your Jenkins or github actions pipeline, its about fast merging changes together. Git branches are counter to this principle, but necessary in order to facilitate change in manageable or deployable chunks. Good Engineers understand CI is a principle, not a build system, this help them focus on it’s purpose which is moving fast an efficiently.

Continuous Deployment (CD) key skills here include understanding deployment strategies like blue-green deployments or canary releases, which minimize risk and downtime during updates. Engineers need to be proficient in infrastructure-as-code tools like Helm, Terraform or CloudFormation to manage their infrastructure alongside their application code. They should also be familiar with containerization technologies like Docker and orchestration platforms like Kubernetes, which can greatly simplify the process of deploying and scaling applications.

Feature Flags have become an essential tool in modern CD practices. They allow teams to decouple code deployment from feature release, giving more control over when and to whom new features are made available. Engineers need to understand how to implement feature flag systems, which can range from simple configuration files to more complex, dynamically controllable systems. This involves not just the technical implementation, but also understanding the strategic use of feature flags for A/B testing, gradual rollouts, and quick rollbacks in case of issues. Proper use of feature flags can significantly reduce the risk associated with deployments and allow for more frequent, smaller releases.

The benefits of mastering CI/CD are significant. It allows teams to deliver value to users more quickly, reduce the risk associated with each deployment, and spend less time on manual, error-prone deployment processes. It also improves developer productivity and satisfaction by providing quick feedback on code changes and reducing the stress associated with large, infrequent releases.

Cross-Platform Development

In today’s diverse technological landscape, users access digital products through a multitude of devices and platforms. As a result, the ability to develop cross-platform solutions has become an increasingly valuable skill for product engineers.

Responsive Web Design (RWD) forms the foundation of cross-platform web development. It’s an approach to web design that makes web pages render well on a variety of devices and window or screen sizes. The core principle of RWD is flexibility – layouts, images, and cascading style sheet media queries are used to create a fluid design that adapts to the user’s screen size and orientation. They should also understand the principles of mobile-first design, which advocates for designing for mobile devices first and then progressively enhancing the design for larger screens.

Cross-Platform Frameworks have emerged for native mobile development as a popular solution for building mobile apps that can run on multiple platforms with a single codebase. Tools like React Native, Flutter and even Web View allow developers to write code once and deploy it to both iOS and Android, potentially saving significant development time and resources.

Proficiency in cross-platform frameworks requires not just knowledge of the framework itself, but also an understanding of the underlying mobile platforms. Engineers need to know when to use platform-specific code for certain features and how to optimize performance for each platform.

The choice between these different approaches – responsive web, native apps, cross-platform frameworks, or even PWAs – depends on various factors including the target audience, required features, performance needs, and development resources. Engineers need to understand the trade-offs involved in each approach and be able to make informed decisions based on the specific requirements of each project.

Moreover, the field of cross-platform development is rapidly evolving. New tools and frameworks are constantly emerging, and existing ones are regularly updated with new features. For example, Flutter has expanded beyond mobile to support web and desktop platforms as well. React Native is used in the PS5 UI now expanding its reach to home entertainment.

This constant evolution means that cross-platform development skills require ongoing learning and adaptation. Engineers need to stay updated with the latest developments in this field, continuously evaluating new tools and approaches to determine if they can provide benefits for their projects.

Conclusion

These technical skills – data analysis, performance optimization, security and privacy, scalability and reliability, CI/CD, and cross-platform development – form the backbone of an engineer’s technical toolkit. Combined with the non-technical skills we discussed in our previous post, they enable engineers to build products that are not only technically sound but also user-friendly, scalable, and aligned with business goals.

Remember, the field of product engineering is constantly evolving. The most successful engineers are those who commit to lifelong learning, always staying curious and open to new technologies and methodologies.

What technical skills have you found most valuable in your product engineering journey? How do you stay updated with the latest trends and technologies? Share your experiences and tips in the comments below!