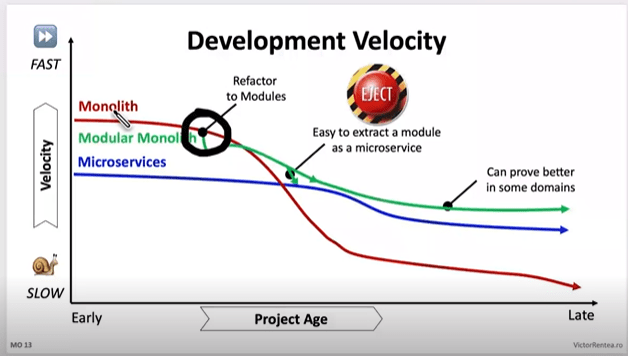

In our previous post, we explored how to identify business domains in your monolith and create a plan for splitting. Now, let’s dive into the strategies for executing this plan effectively. We’ll cover modularization techniques, handling ongoing development during the transition, and measuring your progress.

If you are in the early stages of the chart, you can probably look into Modularization, if you are however towards the right hand side (like we were), you will need to take some more drastic action.

If you are on the right hand side, they your monolith is at the point you need to stop writing code there NOW.

There’s 2 things to consider:

- for new domains, or significant new features in existing domains start them outside straight away

- for existing domains, build a new system for each of them, and move the code out

Once your code is in a new system, you get all the benefits straight away on that code. You aren’t waiting for an entire system to migrate before you see results to your velocity. This is why we say start with the high volume change areas and domains first.

How to stop writing code there “now”? Apply the open closed principle at the system level

- Open for extension: Extend functionality by consuming events and calling APIs from new systems

- Closed for modification: Limit changes to the monolith, aim to get to the point where it’s only crucial bug fixes

This pattern encourages you to move to the new high development velocity systems.

Modularization: The First Step for those on the Left of the chart

Before fully separating your monolith into distinct services, it’s often beneficial to start with modularization within the existing system. This approach, sometimes called the “strangler fig pattern,” can be particularly effective for younger monoliths.

Modularization is a good strategy when:

- Your monolith is relatively young and manageable

- You want to gradually improve the system’s architecture without a complete overhaul

- You need to maintain the existing system while preparing for future splits

However, be wary of common pitfalls in this process:

- Avoid over-refactoring; focus on creating clear boundaries between modules

- Ensure your modularization efforts align with your identified business domains

For ancient monoliths with extremely slow velocity, a more drastic “lift and shift” approach into a new system is recommended.

Integrating New Systems with the Monolith, for those to the Right

When new requirements come in, especially for new domains, start implementing them in new systems immediately. This approach helps prevent your monolith from growing further while you’re trying to split it.

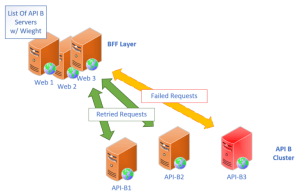

Integrating new systems with your monolith requires these considerations:

- Add events for everything that happens in your monolith, especially around data or state changes

- Listen to these events from new systems

- When new systems need to call back to the monolith, use the monolith’s APIs

This event-driven approach allows for loose coupling between your old and new systems, facilitating a smoother transition.

Existing Domains: The Copy-Paste Approach for those to the Right

If your monolith is in particularly bad shape, sometimes the best approach is the simplest, build a new system then copy, paste, and call it step one from the L7 router. Don’t get bogged down trying to improve everything right away. Focus on basic linting and formatting, but avoid major refactoring or upgrades at this stage. The goal is to get the code into the new system first, then improve it incrementally.

However, this approach comes with its own set of challenges. Here are some pitfalls to watch out for:

Resist the urge to upgrade everything: A common mistake is trying to upgrade frameworks or libraries during the split. For example, one team, 20% into their split, decided to upgrade React from version 16 to 18 and move all tests from Enzyme to React Testing Library in the new system. This meant that for the remaining 80% of the code, they not only had to move it but also refactor tests and deal with breaking React changes. They ended up reverting to React 16 and keeping Enzyme until further into the migration.

Remember the sooner your code gets into the new system the sooner you get faster.

Don’t ignore critical issues: While the “just copy-paste” approach can be efficient, it’s not an excuse to ignore important issues. In one case, a team following this advice submitted a merge request that contained a privilege escalation security bug, which was fortunately caught in code review. When you encounter critical issues like security vulnerabilities, fix them immediately – don’t wait.

Balance speed with improvements: It’s okay to make some improvements as you go. Simple linting fixes that can be auto-applied by your IDE or refactoring blocking calls into proper async/await patterns are worth the effort. It’s fine to spend a few extra hours on a multi-day job to make things a bit nicer, as long as it doesn’t significantly delay your migration.

The key is to find the right balance. Move quickly, but don’t sacrifice the integrity of your system. Make improvements where they’re easy and impactful, but avoid getting sidetracked by major upgrades or refactors until the bulk of the migration is complete.

Measuring Progress and Impact: Part 1 Velocity

Your goal is to have business impact, impact comes from the velocity game to start with, so taht’s where our measurements start.

Number of MRs on new vs old systems: Initially, focus on getting as many engineers onto the new (high velocity) systems as possible, compare your number of MRs on old vs new over time and monitor the change to make sure you are having the impact here first

Overall MR growth: If the total number of MRs across all systems is growing significantly, it might indicate incorrect splitting or dragging incremental work.

Work tracking across repositories: Ask engineers to use the same JIRA ID (or equivalent) for related work across repositories in the branch name or MR Title or something, to track units of work spanning both old and new systems.

Velocity Metrics on old vs new: Don’t “assume” your new systems will always be better, compare old vs new on velocity metric and make sure you are seeing the difference.

Ok, now when you ht critical mass on the above, for us we called it at about 80%, you will need to shift, the long tail there will be less ROI on velocity, it’ll become a support game, and you need to face it differently.

Measuring Progress and Impact: Part 2 Traffic

So at this time its best to look at traffic, moving high volume traffic pages/endpoints in theory should reduce the impact if there’s an issue with the legacy system thereby reducing the support, this might not be true for your systems, you may have valuable endpoints with low traffic, so you need to work it out the best way for you.

Traffic distribution: Looking per page or per endpoint where the biggest piece of the pie is.

Low Traffic: Looking per page or per endpoint where there is low traffic, this may lead you to find features you can deprecate.

As you move functionality to new services, you may discover features in the monolith that are rarely used. Raise with product and stakeholders, ask “Whats the value this brings vs the effort to migrate and maintain it?”

- deprecating the page or endpoint

- combining functionality into other similar pages/endpoints to reduce codebase size

Remember, every line of code you don’t move is a win for your migration efforts.

Conclusion

Splitting a monolith is a complex process that requires a strategic approach tailored to your system’s current state. Whether you’re dealing with a younger, more manageable monolith or an ancient system with slow velocity, there’s a path forward.

The key is to stop adding to the monolith immediately, start new development in separate systems, and approach existing code pragmatically – sometimes a simple copy-paste is the best first step. As you progress, shift your focus from velocity metrics to traffic distribution and support impact.

Remember, the goal is to improve your system’s overall health and development speed. By thoughtfully planning your split, building new features in separate systems, and closely tracking your progress, you can successfully transition from a monolithic to a microservices architecture.

In our next and final post of this series, we’ll discuss how to finish strong, including strategies for cleaning up your codebase, maintaining momentum, and ensuring you complete the splitting process. Stay tuned!