In the world of software development, we often focus on code quality as the primary measure of a product’s health. While clean, efficient code with passing tests is crucial, it’s not the only factor that determines the success of a product. As a product engineer, it’s essential to look beyond the code and understand how to measure the overall health of your product. In this post, we’ll explore some key metrics and philosophies that can help you gain a more comprehensive view of your product’s performance and impact.

The “You Build It, You Run It” Philosophy

Before diving into specific metrics, it’s important to understand the philosophy that underpins effective product health measurement. We follow the principle of “You Build It, You Run It.” This approach empowers developers to take ownership of their products not just during development, but also in production. It creates a sense of responsibility and encourages a deeper understanding of how the product performs in real-world conditions.

What Can We Monitor?

When it comes to monitoring product health, there are several areas we usually focus on:

- Logs: Application, web server, and system logs

- Metrics: Performance indicators and user actions

- Application Events: State changes within the application

While all these are important, it’s crucial to understand the difference between logs and metrics, and when to use each.

The Top-Down View: What Does Your Application Do?

One of the most important questions to ask when measuring product health is: “What does my application do?” This top-down approach helps you focus on the core purpose of your product and how it delivers value to users. So ultimatelly when this value is impacted you know when to act.

Example: E-commerce Website

Let’s consider an e-commerce website. At its core, the primary function of such a site is to facilitate orders. That’s the ultimate goal – to guide users through the funnel to complete a purchase.

So, how do we use this for monitoring? We ask two key questions:

- Is the application successfully processing orders?

- How often should it be processing orders, and is it meeting that frequency right now?

How to Apply This?

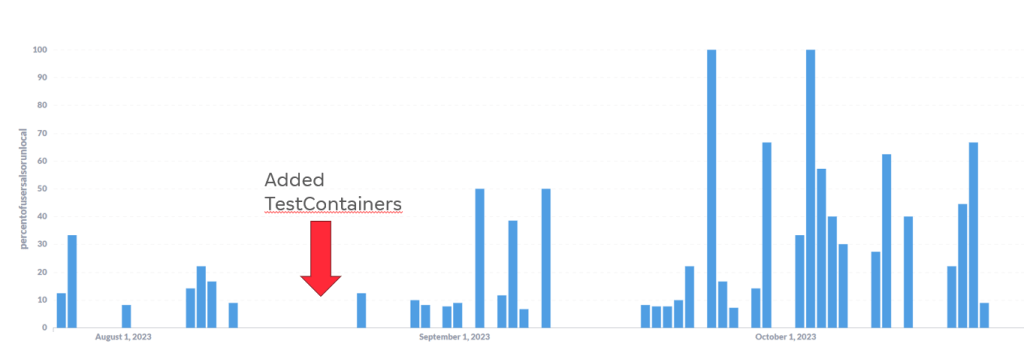

To monitor this effectively, we generally look at 10-minute windows throughout the day (for example, 8:00 to 8:10 AM). For each window, we calculate the average number of orders for that same time slot on the same day of the week over the past four weeks. If the current number falls below this average, it triggers an alert.

This approach is more nuanced and effective than setting static thresholds. It naturally adapts to the ebb and flow of traffic throughout the day and week, reducing false alarms while still catching significant drops in performance. By using dynamic thresholds based on historical data, you’re less likely to get false positives during normally slow periods, yet you remain sensitive enough to catch meaningful declines in performance.

One of the key advantages of this method is that it avoids the pitfalls of static thresholds. With static thresholds, you often face a dangerous compromise. To avoid constant alerts during off-hours or naturally slow periods, you might set the threshold very low. However, this means you risk missing important issues during busier times. Our dynamic approach solves this problem by adjusting expectations based on historical patterns.

While we typically use 10-minute windows, you can adjust this based on your needs. For systems with lower volume, you might use hourly or even daily windows. This will make you respond to problems more slowly in these cases, but you’ll still catch significant issues. The flexibility allows you to tailor the system to your specific product and business needs.

Another Example: Help Desk Chat System

Let’s apply our core question – “What does this system DO?” – to a different type of application: a help desk chat system. This question is crucial because it forces us to step back from the technical details and focus on the fundamental purpose of the system adn teh value it delviers to the business and ultimately the customer.

So, what does a help desk chat system do? At its most basic level, it allows communication between support staff and customers. But let’s break that down further:

- It enables sending messages

- It displays these messages to the participants

- It presents a list of ongoing conversations

Now, you might be tempted to say that sending messages is the primary function, and you’d be partly right. But remember, we’re thinking about what the system DOES, not just how it does it.

With this in mind, how might we monitor the health of such a system? While tracking successful message sends is important, it might not tell the whole story, especially if message volume is low. We should also consider monitoring:

- Successful page loads for the conversation list (Are users able to see their ongoing chats?)

- Successful loads of the message window (Can users access the core chat interface?)

- Successful resolution rate (Are chats leading to solved problems?)

By expanding our monitoring beyond just message sending, we get a more comprehensive view of whether the system is truly doing what it’s meant to do: helping customers solve their problems efficiently.

This example illustrates why it’s so important to always start with the question, “What does this system DO?” It guides us towards monitoring metrics that truly reflect the health and effectiveness of our product, rather than just its technical performance.

A 200 Ok response, is not always OK

As you consider your own systems, always begin with this fundamental question. It will lead you to insights about what you should be measuring and how you can ensure your product is truly serving its purpose.

The Bottom-Up View: How Does Your Application Work?

While the top-down view focuses on the end result, the bottom-up approach looks at the internal workings of your application. This includes metrics such as:

- HTTP requests (response time, response code)

- Database calls (response time, success rate)

Modern systems often collect these metrics through contactless telemetry, reducing the need for custom instrumentation.

Prioritizing Alerts: When to Wake Someone Up at 3 AM

A critical aspect of product health monitoring is knowing when to escalate issues. Ask yourself: Should the Network Operations Center (NOC) call you at 3 AM if a server has 100% CPU usage?

The answer is no – not if there’s no business impact. If your core business functions (like processing orders) are unaffected, it’s better to wait until the next day to address the issue.

Using Loss as a Currency for Prioritization

Once you’ve established a health metric for your system and can compare current performance against your 4-week average, you gain a powerful tool: the ability to quantify “loss” during a production incident. This concept of loss can become a valuable currency in your decision-making process, especially when it comes to prioritizing issues and allocating resources.

Imagine your e-commerce platform typically processes 1000 orders per hour during a specific time window, based on your 4-week average. During an incident, this drops to 600 orders. You can now quantify your loss: 400 orders per hour. If you know your average order value, you can even translate this into a monetary figure. This quantification of loss becomes your currency for making critical decisions.

With this loss quantified, you can now make more informed decisions about which issues to address first. This is where the concept of “loss as a currency” really comes into play. You can compare the impact of multiple ongoing issues, justify allocating more resources to high-impact problems, and make data-driven decisions about when it’s worth waking up engineers in the middle of the night.

Reid Hoffman, co-founder of LinkedIn, once said, “You won’t always know which fire to stamp out first. And if you try to put out every fire at once, you’ll only burn yourself out. That’s why entrepreneurs have to learn to let fires burn—and sometimes even very large fires.” This wisdom applies perfectly to our concept of using loss as a currency. Sometimes, you have to ask not which fire you should put out, but which fires you can afford to let burn. Your loss metric gives you a clear way to make these tough decisions.

This approach extends beyond just immediate incident response. You can use it to prioritize your backlog, make architectural decisions, or even guide your product roadmap. When you propose investments in system improvements or additional resources, you can now back these proposals with clear figures showing the potential loss you’re trying to mitigate, all be it with a pitch of crytal ball about how likely these incident are to occura gain sometimes.

By always thinking in terms of potential loss (or gain), you ensure that your team’s efforts are always aligned with what truly matters for your business and your users. You create a direct link between your technical decisions and your business outcomes, ensuring that every action you take is driving towards real, measurable impact.

Remember, the goal isn’t just to have systems that run smoothly from a technical perspective. It’s to have products that consistently deliver value to your users and meet your business objectives. Using loss as a currency helps you maintain this focus, even in the heat of incident response or the complexity of long-term planning.

In the end, this approach transforms the abstract concept of system health into a tangible, quantifiable metric that directly ties to your business’s bottom line.

Conclusion: A New Perspective on Product Health

As we’ve explored throughout this post, measuring product health goes far beyond monitoring code quality or individual system metrics. It requires a holistic approach that starts with a fundamental question: “What does our system DO?” This simple yet powerful query guides us toward understanding the true purpose of our products and how they deliver value to users.

By focusing on core business metrics that reflect this purpose, we can create dynamic monitoring systems that adapt to the natural ebbs and flows of our product usage. This approach, looking at performance in time windows compared to 4-week averages, allows us to catch significant issues without being overwhelmed by false alarms during slow periods.

Perhaps most importantly, we’ve introduced the concept of using “loss” as a currency for prioritization. This approach transforms abstract technical issues into tangible business impacts, allowing us to make informed decisions about where to focus our efforts. As Reid Hoffman wisely noted, we can’t put out every fire at once – we must learn which ones we can let burn. By quantifying the loss associated with each issue, we gain a powerful tool for making these crucial decisions.

This loss-as-currency mindset extends beyond incident response. It can guide our product roadmaps, inform our architectural decisions, and help us justify investments in system improvements. It creates a direct link between our technical work and our business outcomes, ensuring that every action we take drives towards real, measurable impact.

Remember, the ultimate goal isn’t just to have systems that run smoothly from a technical perspective. It’s to have products that consistently deliver value to our users and meet our business objectives.

As you apply these principles to your own systems, always start with that core question: “What does this system DO?” Let the answer guide your metrics, your monitoring, and your decision-making. In doing so, you’ll not only improve your product’s health but also ensure that your engineering efforts are always aligned with what truly matters for your business and your users.