Introduction

In the world of modern software development, Dependency Injection (DI) has become an essential technique for building maintainable, testable, and scalable applications. By allowing us to decouple our code and manage object lifecycles effectively, DI has revolutionized how we structure our applications.

However, as projects grow in size and complexity, even the most beneficial practices can become challenging to manage. This is especially true for large-scale applications with hundreds of developers and thousands of components. At Agoda, we faced this exact challenge with our dependency injection setup, and we’d like to share how we overcame it.

In this post, we’ll explore the problems we encountered with traditional DI approaches at scale, and introduce Agoda.IoC, our open-source solution that has transformed how we handle dependency injection across our codebase.

The Problem: DI at Scale

To understand the magnitude of the challenge we faced, let’s first consider the scale at which Agoda operates its customer facing website:

- In an average month, we merge over 260 pull requests

- We add more than 38,000 lines of code

- We have around 100 active engineers contributing to our codebase

Stats from 2021

With such a large and active development environment, our traditional approach to dependency injection began to show its limitations. Like many .NET projects, we were using the built-in DI container, registering our services in the Startup.cs file or through extension methods. It looked something like this:

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddSingleton<IService, Service>();

services.AddTransient<IRepository, Repository>();

// ... hundreds more registrations

}

While this approach works well for smaller projects, we encountered several significant issues as our codebase grew:

- Merge Conflicts: With numerous developers working on different features, all needing to register new services, our Startup.cs file became a constant source of merge conflicts. This slowed down our development process and created unnecessary friction.

- Lack of Visibility into Object Lifecycles: As our registration code grew and was split into multiple methods and even separate files, it became increasingly difficult for developers to understand the lifecycle of a particular service without digging through configuration code. This lack of visibility could lead to subtle bugs, especially when dealing with scoped or singleton services that might inadvertently capture user-specific data.

- Maintenance Nightmare: Our main configuration class ballooned to nearly 4,000 lines of code at its peak. This made it incredibly difficult to maintain, understand, and modify our DI setup.

These issues were not just minor inconveniences. They were actively hindering our ability to develop and release products quickly and reliably. We needed a solution that would allow us to scale our dependency injection along with our codebase and team size.

The “Just Break It Up” Approach

When faced with a massive configuration file, the knee-jerk reaction is often to break it up into smaller pieces. This might look something like this:

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddDataServices()

.AddBusinessServices()

.AddInfrastructureServices();

// ... more method calls

}

public static class ServiceCollectionExtensions

{

public static IServiceCollection AddDataServices(this IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddSingleton<IDatabase, Database>();

services.AddTransient<IUserRepository, UserRepository>();

// ... more registrations

return services;

}

// ... more extension methods

}

This pattern can make your Startup.cs look cleaner, but it’s really just hiding the complexity rather than addressing it. The registration logic is still centralized, just in different files. This can actually make it harder to find where a particular service is registered, exacerbating our visibility problem.

Introducing Agoda.IoC

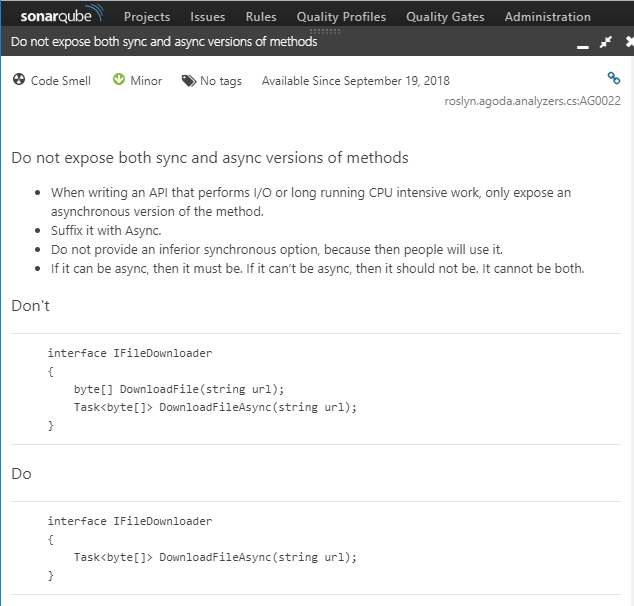

To address the challenges we faced with dependency injection at scale, we developed Agoda.IoC, an open-source C# IoC extension library. Agoda.IoC takes a different approach to service registration, moving away from centralized configuration and towards a more distributed, attribute-based model. In building it we also pulled out a bunch of complex but handy registration patterns we found in use.

Agoda.IoC uses C# attributes to define how services should be registered with the dependency injection container. This approach brings several benefits:

- Decentralized Configuration: Each service is responsible for its own registration, reducing merge conflicts and improving code organization.

- Clear Visibility of Lifecycles: The lifetime of a service is immediately apparent when viewing its code.

- Simplified Registration Process: No need to manually add services to a configuration file; the library handles this automatically.

Let’s look at some examples of how Agoda.IoC works in practice:

Basic Registration

Consider a logging service that you want to use throughout your application:

public interface ILogger {}

[RegisterSingleton]

public class Logger : ILogger {}

This replaces the traditional services.AddSingleton<ILogger, Logger>(); in your startup code. By using the [RegisterSingleton] attribute, you ensure that only one instance of Logger is created and used throughout the application’s lifetime. This is ideal for stateless services like loggers, configuration managers, or caching services.

The interface is used to register the class by default.

Factory Registration

Factory registration is useful for services that require complex initialization or depend on runtime parameters. For example, let’s consider a database connection service:

[RegisterSingleton(Factory = typeof(DatabaseConnectionFactory))]

public class DatabaseConnection : IDatabaseConnection

{

private readonly string _connectionString;

public DatabaseConnection(string connectionString)

{

_connectionString = connectionString;

}

// implementation here

}

public class DatabaseConnectionFactory : IComponentFactory<IDatabaseConnection>

{

public IDatabaseConnection Build(IComponentResolver resolver)

{

var config = resolver.Resolve<IConfiguration>();

string connectionString = config.GetConnectionString("DefaultConnection");

return new DatabaseConnection(connectionString);

}

}

This approach allows you to create a DatabaseConnection with a connection string that’s only known at runtime. The factory can use the IComponentResolver to access other registered services (like IConfiguration) to build the connection.

Explicit Interface Registration

When a class implements multiple interfaces but should only be registered for one, explicit interface registration comes in handy. This is particularly useful in scenarios where you’re adapting third-party libraries or creating adapters:

[RegisterTransient(For = typeof(IExternalServiceAdapter))]

public class ExternalServiceAdapter : IExternalServiceAdapter, IDisposable

{

private readonly ExternalService _externalService;

public ExternalServiceAdapter(ExternalService externalService)

{

_externalService = externalService;

}

// IExternalServiceAdapter implementation

public void Dispose()

{

_externalService.Dispose();

}

}

In this case, we only want to register ExternalServiceAdapter as IExternalServiceAdapter, not as IDisposable. This prevents other parts of the application from accidentally resolving this class when they ask for an IDisposable.

Collection Registration

Collection registration is powerful when you have multiple implementations of an interface that you want to use together, such as in a pipeline pattern or for plugin-like architectures. Here’s an example with a simplified order processing pipeline:

public interface IOrderProcessor

{

void Process(Order order);

}

[RegisterSingleton(For = typeof(IOrderProcessor), OfCollection = true, Order = 1)]

public class ValidateOrderProcessor : IOrderProcessor

{

public void Process(Order order)

{

// Validate the order

}

}

[RegisterSingleton(For = typeof(IOrderProcessor), OfCollection = true, Order = 2)]

public class InventoryCheckProcessor : IOrderProcessor

{

public void Process(Order order)

{

// Check inventory

}

}

[RegisterSingleton(For = typeof(IOrderProcessor), OfCollection = true, Order = 3)]

public class PaymentProcessor : IOrderProcessor

{

public void Process(Order order)

{

// Process payment

}

}

With this setup, you can inject IEnumerable<IOrderProcessor> into a service that needs to run all processors in order:

public class OrderService

{

private readonly IEnumerable<IOrderProcessor> _processors;

public OrderService(IEnumerable<IOrderProcessor> processors)

{

_processors = processors;

}

public void ProcessOrder(Order order)

{

foreach (var processor in _processors)

{

processor.Process(order);

}

}

}

This approach allows you to easily add or remove processing steps without changing the OrderService class.

Keyed Registration

Keyed registration allows you to register multiple implementations of the same interface and retrieve them by a specific key. This is particularly useful when you need different implementations based on runtime conditions.

Example scenario: Multiple payment gateways in an e-commerce application.

public interface IPaymentGateway

{

bool ProcessPayment(decimal amount);

}

[RegisterSingleton(Key = "Stripe")]

public class StripePaymentGateway : IPaymentGateway

{

public bool ProcessPayment(decimal amount)

{

// Stripe-specific payment processing logic

return true;

}

}

[RegisterSingleton(Key = "PayPal")]

public class PayPalPaymentGateway : IPaymentGateway

{

public bool ProcessPayment(decimal amount)

{

// PayPal-specific payment processing logic

return true;

}

}

public class PaymentService

{

private readonly IKeyedComponentFactory<IPaymentGateway> _gatewayFactory;

public PaymentService(IKeyedComponentFactory<IPaymentGateway> gatewayFactory)

{

_gatewayFactory = gatewayFactory;

}

public bool ProcessPayment(string gatewayName, decimal amount)

{

var gateway = _gatewayFactory.GetByKey(gatewayName);

return gateway.ProcessPayment(amount);

}

}

In this example, you can switch between payment gateways at runtime based on user preference or other factors.

Mocked Mode for Testing

Agoda.IoC provides a mocked mode that allows you to easily swap out real implementations with mocks for testing purposes. This is particularly useful for isolating components during unit testing.

Example scenario: Testing a user service that depends on a database repository.

public interface IUserRepository

{

User GetUserById(int id);

}

[RegisterSingleton(Mock = typeof(MockUserRepository))]

public class UserRepository : IUserRepository

{

public User GetUserById(int id)

{

// Actual database call

return new User { Id = id, Name = "Real User" };

}

}

public class MockUserRepository : IUserRepository

{

public User GetUserById(int id)

{

// Return a predefined user for testing

return new User { Id = id, Name = "Mock User" };

}

}

public class UserService

{

private readonly IUserRepository _userRepository;

public UserService(IUserRepository userRepository)

{

_userRepository = userRepository;

}

public string GetUserName(int id)

{

var user = _userRepository.GetUserById(id);

return user.Name;

}

}

When running in normal mode, the real UserRepository will be used. In mocked mode (typically during testing), the MockUserRepository will be injected instead, allowing for predictable test behavior without actual database calls.

Open Generic Service Registration

Agoda.IoC supports registration of open generic services, which is particularly useful when you have a generic interface with multiple implementations.

Example scenario: A generic repository pattern in a data access layer.

public interface IRepository<T> where T : class

{

T GetById(int id);

void Save(T entity);

}

[RegisterTransient(For = typeof(IRepository<>))]

public class GenericRepository<T> : IRepository<T> where T : class

{

public T GetById(int id)

{

// Generic implementation

}

public void Save(T entity)

{

// Generic implementation

}

}

// Usage

public class UserService

{

private readonly IRepository<User> _userRepository;

public UserService(IRepository<User> userRepository)

{

_userRepository = userRepository;

}

// Service implementation

}

With this setup, Agoda.IoC will automatically create and inject the appropriate GenericRepository<T> when an IRepository<T> is requested for any type T.

These advanced features of Agoda.IoC provide powerful tools for handling complex dependency injection scenarios, from runtime-determined implementations to easier testing and support for generic patterns. By leveraging these features, you can create more flexible and maintainable application architectures.

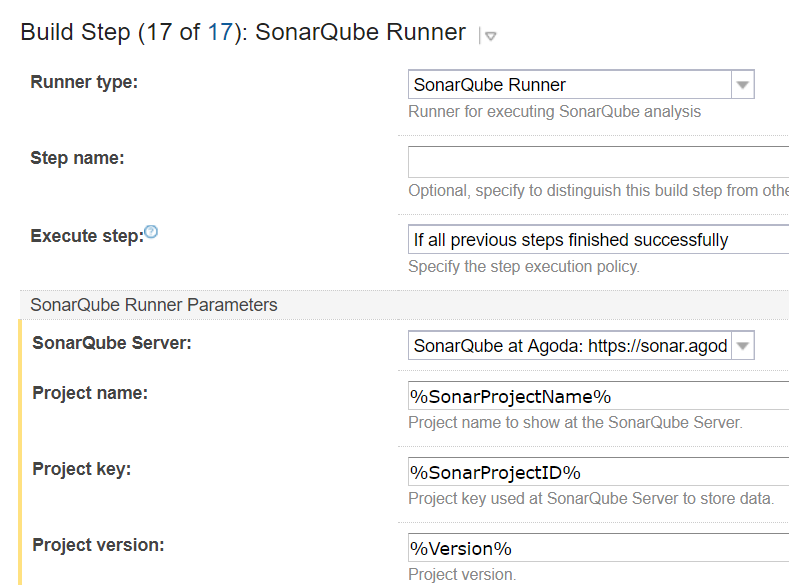

Implementing Agoda.IoC in Your Project

Now that we’ve explored the features and benefits of Agoda.IoC, let’s walk through the process of implementing it in your .NET project. This guide will cover installation, basic setup, and the migration process from traditional DI registration.

First, you’ll need to install the Agoda.IoC package. You can do this via the NuGet package manager in Visual Studio or by running the following command in your project directory:

dotnet add package Agoda.IoC.NetCore

Basic Setup

Once you’ve installed the package, you need to set up Agoda.IoC in your application’s startup code. The exact location depends on your project structure, but it’s typically in the Startup.cs file for traditional ASP.NET Core projects or in Program.cs for minimal API projects.

For a minimal API project (Program.cs):

using Agoda.IoC.NetCore;

var builder = WebApplication.CreateBuilder(args);

// Your existing service configurations...

// Add this line to set up Agoda.IoC

builder.Services.AutoWireAssembly(new[] { typeof(Program).Assembly }, isMockMode: false);

var app = builder.Build();

// ... rest of your program

The AutoWireAssembly method takes two parameters:

- An array of assemblies to scan for registrations. Typically, you’ll want to include your main application assembly.

- A boolean indicating whether to run in mock mode (useful for testing, as we saw in the advanced features section).

Before:

// In Startup.cs

services.AddSingleton<IEmailService, EmailService>();

services.AddTransient<IUserRepository, UserRepository>();

services.AddScoped<IOrderProcessor, OrderProcessor>();

// In your classes

public class EmailService : IEmailService { /* ... */ }

public class UserRepository : IUserRepository { /* ... */ }

public class OrderProcessor : IOrderProcessor { /* ... */ }

After:

// In Startup.cs

services.AutoWireAssembly(new[] { typeof(Startup).Assembly }, isMockMode: false);

// In your classes

[RegisterSingleton]

public class EmailService : IEmailService { /* ... */ }

[RegisterTransient]

public class UserRepository : IUserRepository { /* ... */ }

[RegisterPerRequest] // This is equivalent to AddScoped

public class OrderProcessor : IOrderProcessor { /* ... */ }

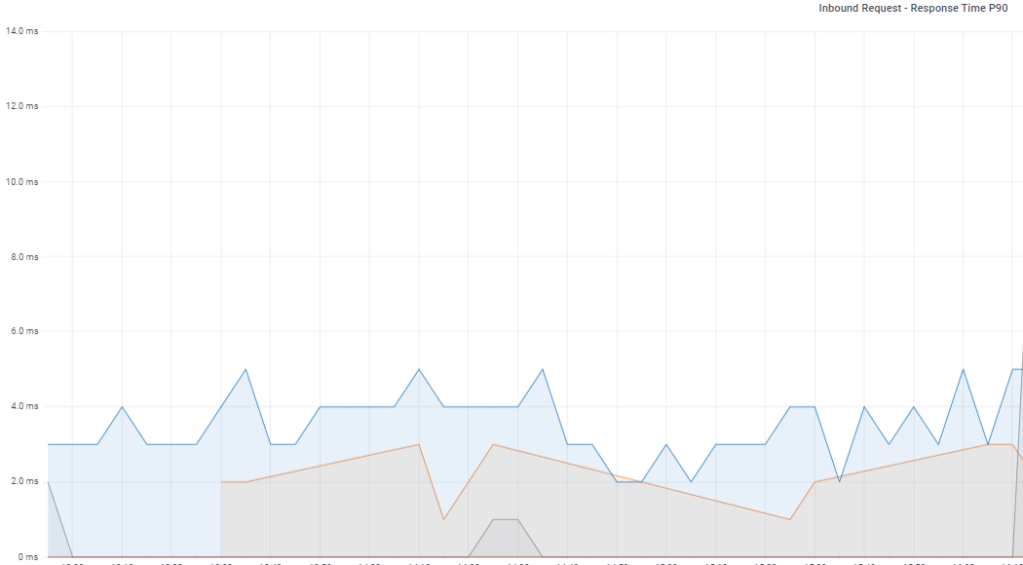

The Reflection Concern

When introducing a new library into a project, especially one that uses reflection, it’s natural to have concerns about performance.

The key point to understand is that Agoda.IoC primarily uses reflection during application startup, not during runtime execution. Here’s how it breaks down:

- Startup Time: Agoda.IoC scans the specified assemblies for classes with registration attributes. This process happens once during application startup.

- Runtime: Once services are registered, resolving dependencies uses the same mechanisms as the built-in .NET Core DI container. There’s no additional reflection overhead during normal application execution.

Agoda.IoC.Generator: Enhancing Performance with Source Generators

While the reflection-based approach of Agoda.IoC is performant for most scenarios, we understand that some projects, especially those targeting AOT (Ahead-of-Time) compilation, may require alternatives. This is where Agoda.IoC.Generator comes into play.

To use Agoda.IoC.Generator, you simply need to add it to your project alongside Agoda.IoC. The source generator will automatically detect the Agoda.IoC attributes and generate the appropriate registration code.

By offering both reflection-based and source generator-based solutions, we ensure that Agoda.IoC can meet the needs of a wide range of projects, from traditional JIT-compiled applications to those requiring AOT compilation.

Conclusion: Embracing Agoda.IoC for Scalable Dependency Injection

As we’ve explored throughout this blog post, dependency injection is a crucial technique for building maintainable and scalable applications. However, as projects grow in size and complexity, traditional DI approaches can become unwieldy. This is where Agoda.IoC steps in.

Let’s recap the key benefits of Agoda.IoC:

- Decentralized Configuration: By moving service registration to attributes on the classes themselves, Agoda.IoC eliminates the need for a centralized configuration file. This reduces merge conflicts and makes it easier to understand the lifecycle of each service.

- Improved Code Organization: With Agoda.IoC, the registration details are right where they belong – with the service implementations. This improves code readability and maintainability.

- Flexibility: From basic registrations to more complex scenarios like keyed services and open generics, Agoda.IoC provides the flexibility to handle a wide range of dependency injection needs.

- Testing Support: The mocked mode feature makes it easier to write and run unit tests, allowing you to easily swap out real implementations for mocks.

- Performance: Despite using reflection, Agoda.IoC is designed to be performant, with minimal impact on startup time and runtime performance. And for scenarios requiring AOT compilation, Agoda.IoC.Generator provides a source generator-based alternative.

- Scalability: As your project grows from a small application to a large, complex system, Agoda.IoC scales with you, maintaining clean and manageable dependency registration.

At Agoda, we’ve successfully used this library to manage dependency injection in our large-scale applications, handling thousands of services across a team of hundreds of developers. It has significantly reduced the friction in our development process and helped us maintain a clean, understandable codebase even as our systems have grown.

Of course, like any tool, Agoda.IoC isn’t a silver bullet. It’s important to understand your project’s specific needs and constraints. For some smaller projects, the built-in DI container in .NET might be sufficient. For others, especially larger, more complex applications, Agoda.IoC can provide substantial benefits.

We encourage you to give Agoda.IoC a try in your projects. Start with the basic features, and as you become more comfortable, explore the advanced capabilities like keyed registration and collection registration. We believe you’ll find, as we have, that it makes managing dependencies in large projects significantly easier and more maintainable.

In the end, the goal of any development tool or practice is to make our lives as developers easier and our code better. We believe Agoda.IoC does just that for dependency injection in .NET applications. We hope you’ll find it as useful in your projects as we have in ours.